Whose Story Is Told: Lived Religion and the Jewish Digital Artifacts of the Pandemic

Vanessa Ochs

Please DON’T DELETE that email from your rabbi offering to Zoom the Shabbat service straight into your lounge. SAVE that notice from the kosher supermarket reassuring customers that there will be enough matzah for Passover. DOWNLOAD your synagogue’s poster offering support for vulnerable people in the community. BOOKMARK Hamodia, an Orthodox online newspaper, branding itself as ‘your coronavirus info hub.’ The community that ostensibly frowns upon the internet is finally harnessing its power to collate and publicize rabbinic statements to close down synagogues and Jewish schools...These items deserve to be collected as they will tell a story of resilience and creativity: fortunately, we have the perfect central repository for this information. The National Library of Israel [NLI] is creating the COVID-19 Jewish ephemera collection.-- Sally Berkovic, A Digital Geniza: Collecting COVID-19 Ephemera, The Times of Israel March 22, 2020

Shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic sent us into quarantine, when we were assembling tentative masks out of folded-over table napkins, and we were googling to see if we could make kosher matzot for Passover in our own homes, historians, archivists, and museum professionals around the world were already broadcasting the messages Sally Berkovic reported on in The Times of Israel: Save everything and anything, including oral histories, including images on your screen, that could chronicle Jewish life now and send it to a digital repository. What a lark, and we were bored or at our nerves end anyways, so sending materials or signing up to be interviewed for an oral history project about our pandemic experience thus far would be a diversion, distraction, possibly even from the sickbed or from mourning. The impulse behind these archival efforts recalls the practice of collection and preservation of As-sky and Peretz, who embarked upon ethnographic expeditions in 1912-14 to gather, while they still could, evidence of Jewish life beyond the Pale. The message of this day was clear: the ephemera of today—largely digital in our age—could become a treasure trove, a virtual geniza that would allow for an eventual informed historical understanding of an unprecedented era.

Collecting organizations in America joined hands: Collecting These Times was a project of The Council of American Jewish Museums (CAJM) and George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media; they were joined by the Breman Museum, the Capital Jewish Museum, Hebrew Theological College, the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and Prizmah: Center for Jewish Day Schools. The grassroots-dependent collecting efforts were readily funded, with support coming from the “Chronicling Funder Collaborative” composed of the Lippman Kanfer Foundation for Living Torah, Jim Joseph Foundation, Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family Philanthropies, and The Russell Berrie Foundation. Similar efforts were inaugurated and funded in Israel, Europe, South Africa, and Australia.

As scholars now begin to study the Jewish pandemic collections, it is certain that one stance will be privileged: the hierarchical gaze which customarily embraces a Jewish triumphal narrative, one focusing on the roles of bold, steadfast leaders (often male) who successfully take their communities through crises and assure Jewish survival. Such an approach taken in the analysis of the diverse pandemic archives would understandably highlight the heroic, thoughtful, selfless, and exhausting efforts of rabbis, cantors, educators, and a diverse array of Jewish communal professionals who truly saved the day by working overtime to sustain many forms of Jewish life, first through one liturgical year, and then another and another. Probably, such a top-down approach would point to how leaders used technology to create and sustain Jewish synagogue and educational experiences that would otherwise have taken place in person and in communal settings. Inadvertently, a hierarchical gaze might highlight the adaptive efforts of wealthier communities in bigger cities that could afford livestream or zoom broadcasts crafted by professional videographers and sound technicians using state of the art equipment. Further, it would likely highlight the agility of organized Jewish communities, even those known to change most slowly, as they swiftly pivoted into pandemic-mode while referencing Jewish values and texts that would facilitate some level of compliance with public safety measures.

In a Jewish context, standard hierarchical narratives have privileged those who know the sacred texts and public rituals and have cultural and political agency to access sources and do the telling. Predictably, rupture and change yield to survival, and even triumph. There is a recurring theme: Judaism will endure even as it is challenged and changed.

Here, I am proposing that scholars who are beginning to analyze the vast repositories of digital materials and oral histories would do well to remember that it is equally important to take a bottom-up approach to studying Jewish life transpiring during the pandemic, one that exists in in private, domestic spaces as well as in in the intersection between communal and private space.

What does it mean to study materials or communities from a lived religion perspective? For a definition, I turn to Robert Orsi, an eminent scholar of lived religion in America. Compared to a study of religion which privileges sacred texts and their interpretations, liturgies, theologies, histories, institutions, and leaders, a lived religion approach, Orsi writes, describes “the varied media in which men, women and children who were formed by inherited, found, made and improvised religions within particular historical, cultural and political contexts engage shared human dilemmas and situations..."[1] Lived religion values and studies the ways that people go about “improvising with the inherited idioms of their traditions—with idioms that constrain them as they enable them to live and change at the same time.” (168) as they “experience and construe events in their social world…and perennial human problems.” Bottom line, for Orsi: “lived religion is “religion as people actually do and imagine it in the circumstances of their everyday lives…” (158).

Looking at the American pandemic collections from a lived religion perspective tells the other half of the story, the parts that a hierarchical gaze glosses over. It would focus on what happens outside of communal spaces that are monitored by professional and lay leaders. It would point, as well, to how communal and domestic spaces are interwoven. A lived religion narrative would not elide the complex lives of everyday people. It would chronicle loss, despair, dislocation; creativity, missteps, fortitude, and striving to maintain the status quo. It tells Jewish stories without presumed endings.

Taking a bottom-up approach—studying “lived religion”—would shine a light on the creative practices and reflections of individual Jews and Jewish families of many sorts, in the privacy of their homes or pods, drawing upon available resources that shape and attempt to sustain Jewish lives. Studying lived religion, scholars might consider the stories of Jewish friends and friendship circles texting images on Fridays of hallahs they were making for the first time, perhaps from a shared source of sourdough starter. They might note that while observant Jews were holding shivas and shloshim gatherings that marked deaths, secular Jews were doing so as well, adapting the practice to their own circles. They might analyze (if anyone had dared to submit the evidence captured on cell phones)— images of backyard Orthodox weddings, large ones, pre-vaccines, pre N-95 masks–that were still held even though they contradicted the public health guidelines ostensibly being followed by their communities.

A lived religion approach yields potentially messy stories.

When analyzing the collections, scholars of lived religion will need to keep their eyes on various biases within the instructions for submission, that may have discouraged certain kinds of submissions and hence, only a partial picture of the era would be chronicled.

Looking at the instructions posted by various collections in the US and abroad, one tends to see an inadvertent privileging of potential contributors who adhere to diverse sets of Jewish standards and expectations that are typically embraced by institutions, rabbinic and community leaders, Jewish educators, Jewish communities, and philanthropic organizations. That might discourage contributions that could appear not to comply with various versions of Jewish standards. Evidence of, say, rebellion, transgression, resistance, messy accommodation, and even despair would potentially be withheld.

I offer several examples of how subtle bias toward hierarchical analysis can creep into the instructions for contributors. The American Jewish Historical Society began an oral history collecting project funded for $75,000 by the Righteous Person’s Foundation called “Towards a Meaningful Snapshot.” It is already available online: one can hear or read transcripts of the interviews of 36 Jews, many of them widely known Jewish communal leaders, with “diverse experiences and perspectives on Covid 19” which, according to the description, will allow people in 100 years from now to look back and tell a “more full, nuanced story of the Jewish response,” one that would “Capture the fear, anxiety and loss as well as hope, creativity and innovation of this moment for generations to come.” That last phrase from the description of the project recalls the trope of rupture, change, survival and even triumph in both Jewish liturgy and Jewish history as it has so often been narrated, hierarchical-style, in broad strokes from the pulpit and in Jewish schools. The standard narrative that privileges those who know the texts and public rituals, have cultural and political agency to access sources, do the telling, and, they have an agenda typically as well: Judaism will endure even as it is challenged and changed. This mode of thinking underscores many of the instructions for submissions.

Here is another example of bias against bottom-up submissions and consequently, the construction of bottom up narratives: it comes from Melbourne Australia, where Jewish artifacts were being housed in the project called “A Journal of the Plague Year,” (title is a play on Defoe’s work), a global effort undertaken with leadership from Arizona State. When potential contributors were invited to submit written reflections on life in quarantine, they were asked to submit “all files associated with this story” meaning “photographs, videos, audio interviews, screenshots, drawings and, memes.” They were prompted, on the submission page, to describe “what the object or story you've uploaded says about the pandemic, and/or why what you've submitted is important to you on the affective level: ‘how does the object make you feel?’”

So far so good, but, perhaps with the caveat that the ability to receive the call to collect in the first place was dependent upon ones having internet access, digital fluency, some free time, and enough physical and mental health. Reading between the lines one can see the insertion of value judgments despite a promise that there will be no judgment:

"You might consider yourself well inside the mainstream community, or you might have no interaction with it, or somewhere in between."

Further: "We are interested in the ways that the lives of individuals and families were affected, the disruptions and adaptations to the daily and weekly cycles of Jewish life."

"How are you and/or your family been adapting your Jewish practices in the circumstances?"

Here, what constitutes a proper Jewish identity and lifestyle has already been predetermined as being inside or outside some set of communal norms. While there may be diverse means of adaptation, there is a shared understanding of what goals must be achieved.

A final example: in YIVO’s call, specifically in some of the questions posed, we see yet another instance of privileging of communal norms that must be upheld. The phrasing assumes that potential contributors are sufficiently versed in their community’s daily and weekly cycles of Jewish life that they appraise disruptions during the pandemic and seek appropriate remedies:

"How has the pandemic affected your Rosh Hashanah?"

"How has the pandemic affected your Yom Kippur?"

"How has the pandemic affected your Sukkot, Simhat Torah and Shemini Atzeret?"

Further, YIVO’s instructions ask: “To what extent have you been able to maintain a meaningful Jewish life while adhering to social distancing guidelines?”

While it is an open matter here as to what constitutes a Jewish life that is meaningful or not, the question, as worded, suggests that all community members can agree upon what constitutes a meaningful Jewish life. Surely, that could exclude those whose submissions might reveal that they were making Jewish meaning in eclectic or non-conforming ways.

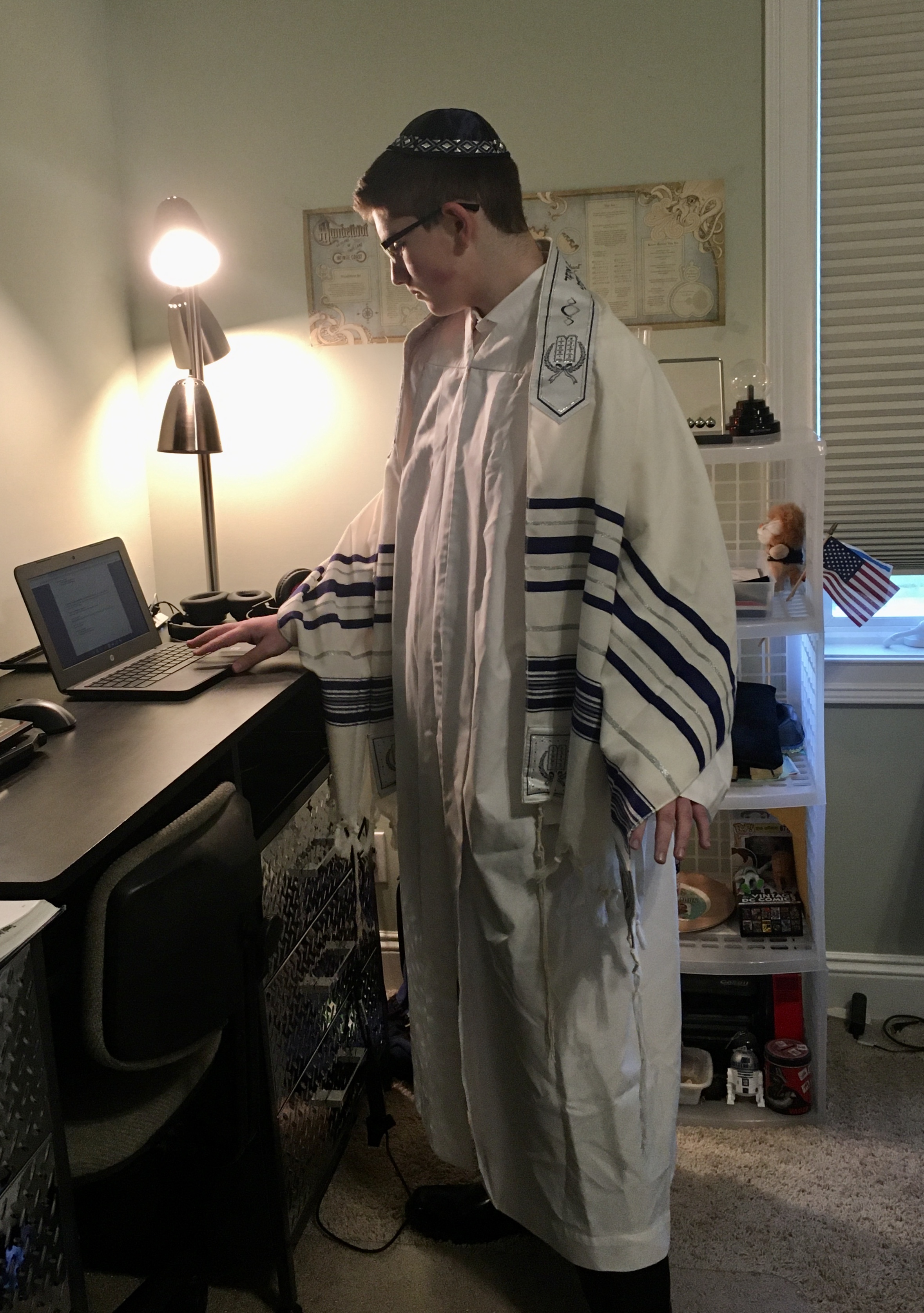

Even with the best intentions, scholars set on taking a lived religion approach can find themselves inadvertently embracing a hierarchical gaze and crafting a hierarchical narrative. This example comes from my own experience. In the spring of 2020, as is often the case, I was not planning to be doing research on contemporary Jewish life, pandemic or otherwise. I was sitting on my living room sofa, “going” virtually to a local Reform synagogue in central Virginia which had already been closed for many weeks. Using my ipad, I “joined” the worshippers at a bat mitzvah, one of the first the community was holding “covid-style” instead of postponing. The community’s rabbis were just learning how to use Zoom and so were the congregants and guests; “mute yourself grandma” was not yet a meme but a plaintive refrain. The focus of the attention of those of us in the Zoom gallery was the scene being captured on a laptop in Bat mitzvah girl’s living room; she, her parents, and siblings were the only ones at what I thought of as the “live” event. The community's rabbis were presiding from their respective living rooms, each taking a turn singing verses of prayers because as we were just learning, you can’t sing together on Zoom. The family was all dressed up in good clothes and even wore shoes they had either purchased before covid or got online; they sat in a row on their sofa, as if it were a pew, and they had that uncomfortable look that says, “it’s weird praying like this at home.” Scanning the images in the gallery, you could pick out close relatives, for they, unlike the local community members, were dressed as if they had actually gone to synagogue.

When it was time for the Torah service, the bat mitzvah family and their laptop shifted from the coffee table over to their dining room for what would be an abbreviated reading. On the table was an already open Torah covered with a tallit. The day before, a rabbi had brought it and the pointer over; it was rolled so that all the family had to do was to remove the tallit and find the pointer at the place where the bat mitzvah girl could chant the passage she had memorized after and before her blessings. The girl did well; the parents gave their speech, too long, but who could not indulge them, if that compensated for this long-anticipated major rite of passage that had to be carried out in a bare-bones, digitally-mediated, family-and-friends-absent way? It was, after all, my first Zoom bat mitzvah, and I was still amazed that even though I was at home, on my couch with a cup of coffee, I still felt all the touching emotions that arose when a young Jewish person in my community, even a stranger, came of age.

Then it was time for the rabbi’s words to the Bat Mitzvah and her family: What the rabbi said in her spontaneous remarks, more or less, was this, and her words were directed to the whole family: “Look—at this difficult time, with all the disappointments, you have succeeded in taking ownership of your Judaism; you have made the Torah your own.” I understood the rabbi to be saying that despite the pandemic, this family–not regular synagogue-goers, not people who would otherwise have found themselves alone, standing alongside an open Torah scroll—had managed to pull off a version of a legitimate Torah service on their own, without rabbis, gabbis, and elders present to guide them through the paces. The Torah was on their own dining room table, and by engaging with it, their daughter had become a bat mitzvah according to the local ritual. They DID IT THEMSELVES, this is DIY Judaism. Initially I noted to myself that while this was real life I was observing and not scholarship, what I had witnessed was a rabbi taking a lived religion approach in appraising a Jewish ritual that had unfolded before her.

But as I went on to analyze the rabbi’s words and called her later that week to find out more about what she meant when she congratulated the family “making the Torah their own,” it became clearer to me that I had been mistaken: what had initially appeared to me to be the rabbi’s bottom-up appraisal was, in fact, a standard hierarchical appraisal. Nearly all that had been accomplished by this family has been dependent on the previous interventions of the clergy and teachers. It was they who prepared the young woman to chant Torah and Haftarah, who taught her to pray, who brought over the Torah and positioned it so it could be property used. It was they who revamped the service and created programmatic cues for themselves so an abbreviated covid shabbat service could actually “work.” Without their interventions, the family could not have had their experience of ownership.

What would a lived religion approach pay attention to in this scenario: one in which a rabbi was not telling Jews how well they succeeded in conforming to rabbinic expectation? One in which the participants themselves had a voice in reflecting on what they had experienced, what they had accomplished, and what it had felt like to them?

In one of the archives, I found an article about a Covid bat mitzvah that vividly spoke to a lived religion approach. “Bat Mitzvah in the Time of COVID-19” by Rachel Simon, the mother of a bat mitzvah, captures a family’s feelings of joy, pride, and connection despite disappointment, loneliness, and fear. The bat mitzvah took place in March of 2020, just days after all the out-of-town guests who had planned to come to town had canceled. It was decided that the service would be live-streamed from their synagogue, one already equipped to do this with only the rabbi and immediate family present.

Simon recounts how she addressed her daughter during the ceremony: “…many times throughout our history, Jews have been forced to chant Torah in isolation, quiet for fear of being punished. It would be easy to look at our strange circumstances today like that, but we are not. Instead, while the seats of this beautiful synagogue may not be filled, your family and friends from all the different parts of your life are here with you, virtually that is. We don’t know about you, but isolated is the last thing that we feel. I hope you feel the same way.”

Simon concludes by sharing the novel way the online congregation, without instruction, used chat room messaging and diverse forms of social media to create connection on that day and afterwards. While it does indeed have a triumphal ending, it is a bottom-up narrative that comes about through the unplanned, unsupervised, and granted, non-halachic, industry of diverse individuals:

“Once the service began, we didn’t think about the empty sanctuary because our hearts were filled with pride. Tears were shed, by everyone in the room. It was as beautiful as we expected. When the service ended we looked at our phones. We had hundreds of notifications — texts, emails, Facebook posts, Instagram tags and Snapchat stories. Abby was so overwhelmed, she started to cry. People sent us screenshots and videos of the service and pictures of them watching from home. We truly felt the power of community and it was inspiring!”

[1]:Robert Orsi, Between Heaven and Earth: The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars Who Study Them (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 168.

Return to Main Page